Court Decisions on wolves and pending cases

A summary of federal classification of gray wolves

Focused on the listed entry of gray wolves nationwide (outside of Alaska and the Northern Rocky Mountains).

2021

Wisconsin state court

21 October 2021, Judge Frost (a WI Dane County, WI circuit court judge) issued a temporary restraining order stopping the issuance of permits for the wolf hunt, which would have started Nov. 6. The state DoJ might choose to appeal on oct 26th or, if not, Judge Frost will move to the next stage, hearing oral arguments about the merits of the case. Judge Frost stopped the issuance of permits because he ruled that the DNR acted unconstitutionally because it did not follow all the terms of Act-169. Act 169 is the law passed in 2012 that obliged the DNR to:

a) hold a wolf hunt every year (provided wolves were not on endangered species list), AND

b) formalize a new management plan for wolves. AND

c) pass permanent rules for such wolf hunts.

In short, the judge found the DNR did neither of the last two actions (b and c). Instead, the DNR has been relying on nine-year-old emergency rules and a 22-year-old management plan.

The judge’s order that stopped the wolf-hunt is temporary pending his hearing of the oral arguments on each side so more news will come and we have to keep up the fight for just, science-based wolf management and good governance.

Federal court in the District of Wisconsin (pending)

The tribal lawsuit (Red Cliff & eight allied tribes) will be considered on Oct 29th; that's when a federal court will rule on their request for a temporary injunction on the hunt. This case is different than #1 above because federal laws supersede state laws. The tribes allege that their federal treaty rights were infringed in the way the wolf hunt rules were established in 2021. If the tribes succeed in this lawsuit, their legal right to consultation will be strengthened. (They want to be fully consulted on wolf hunting so they can protect Ma’iingan (brother wolf) from hunts like that in Feb 2021). If the state wins this case, the process used in 2021 for deciding both wolf hunts (Feb and the upcoming one in Nov) will become the status quo.

Meanwhile, the Kansas-based group ‘Hunter Nation’, that sued successfully in Jefferson Co. court, to compel the DNR to hold the hunt in Feb 2021 might still be in play. Their lawsuit is still not closed, and they have tried to intervene in case #1 (above). Their intervention was rejected on Thursday, Oct 21. We will see what their next move is.

Federal court cases pending on nationwide gray wolf delisting

Last, there are two federal lawsuits still pending (to be heard in November, filed by the major plaintiff NGOs of the past including the Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife, Earth Justice, U.S. Humane Society, etc. If the plaintiffs succeed, wolves would be put back on the endangered list. Here, the US Fish & Wildlife Service (within the dept of interior) will be attempting to keep them off the list.

2003-2020 Federal decisions

Stay posted. Under construction. See our page on the scientific peer review ere.

2017 On Appeal: Humane Society v. Jewell (D.D.C.)

The government appealed the relisting by Judge Howell (below) and lost on appeal.

2014 Humane Society v. Jewell (D.D.C.)

>See through the rhetoric by reading the actual decision by the judge.

Summary: Canis lupus first received ESA protection as an entire species in 1978, when FWS listed all gray wolves in two populations: one in Minnesota listed as threatened, and one listed as endangered in all other 47 coterminous states. Because the ESA did not at that time contain the term “distinct population segment” (DPS) within the definition of “species,” FWS considered the two populations to be separate “species” for listing purposes and applied the five listing criteria to each population separately.

In 2011, FWS issued a rule in its fourth attempt to delist wolves in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan. The mechanism FWS used to accomplish the delisting was to “revise” the existing listing for Minnesota gray wolves to establish it as the Western Great Lakes (WGL) DPS, to expand the boundaries of that DPS beyond Minnesota to eight other Midwestern states, and then to remove that DPS from ESA protection. FWS concluded that the WGL wolves were not in danger of extinction nor likely to become so in the foreseeable future, throughout all or a significant part of their range, with that range defined by the borders of the DPS. This rule became effective on January 27, 2012 and was challenged by the HSUS plaintiffs.

The District Court first determined that the plaintiffs had standing to bring the case. Then the court found several separate reasons for invalidating the 2011 delisting rule.

First, the court found that the structure, history and purpose of the ESA do not allow FWS to identify a DPS solely to delist a vertebrate population. The court determined that designating a DPS for the purpose of not listing a vertebrate population makes no sense within the context of the ESA because, to identify a DPS, FWS must first determined that the vertebrates, as a distinct group, are threatened with extinction. Absent that determination, the ESA does not authorize FWS to recognize and create a DPS at all. “In short, the creation or initial designation of a DPS operates as a one-way ratchet to provide ESA protections” to the covered wildlife. The court determined that FWS’ interpretation of the statute was not entitled to any Chevron deference because it directly conflicted with the structure of the statute. The court also held that the Minnesota wolf population was not an extant DPS at the time of the 2011 final rule because FWS had never designated or treated it as such, and it did not and could not meet the requirements set forth in FWS’ DPS Policy. Furthermore, expanding the size and contours of a DPS boundary from a single state to all or part of nine states runs counter to the DPS Policy, which reflects the notion that a DPS is a generally static designation.

Second, the court found that the ESA does not allow the designation of a DPS made up of vertebrates already protected under the ESA at a more general taxonomic level. Because wolves were already listed at the species level as Canis lupus, the structure and purpose of the ESA prohibit FWS from reducing that protection by manipulating the definition of “species” to treat the DPS animals as if they were a different, unlisted species. Instead of considering the status of the entire listed species as a whole, the 2011 rule impermissibly focused solely on the viability of a single population of wolves in only a part of their historic range. Once FWS lists a species, that species becomes the entity protected under the ESA and the agency’s subsequent actions, whether review or delisting, must address that entire listed entity.

As a third, stand-alone reason for invalidating the rule, the court found that the delisting rule was contrary to the evidence before FWS. FWS failed to explain why territory suitable for wolf occupation is not a significant part of the gray wolf’s range. The court followed Ninth Circuit precedent requiring FWS to explain why territory that is part of a species’ historical range but no longer occupied by that species, falls outside a significant portion of the species’ range for ESA purposes. FWS failed to provide such explanation in the 2011 rule, instead focusing on the species’ status within its current range. FWS also failed to explain the impact of combined mortality factors. The record showed that the WGL wolf population is vulnerable to disease and human-caused mortality, yet FWS failed to address how the two factors could interact to create a clear threat to the species.

In light of its findings, the court determined that the proper remedy was complete vacatur of the 2011 rule. The court ordered vacatur and reinstated the original 1978 rule which provides that gray wolves in Minnesota are listed as threatened and gray wolves in all other coterminous states are endangered.

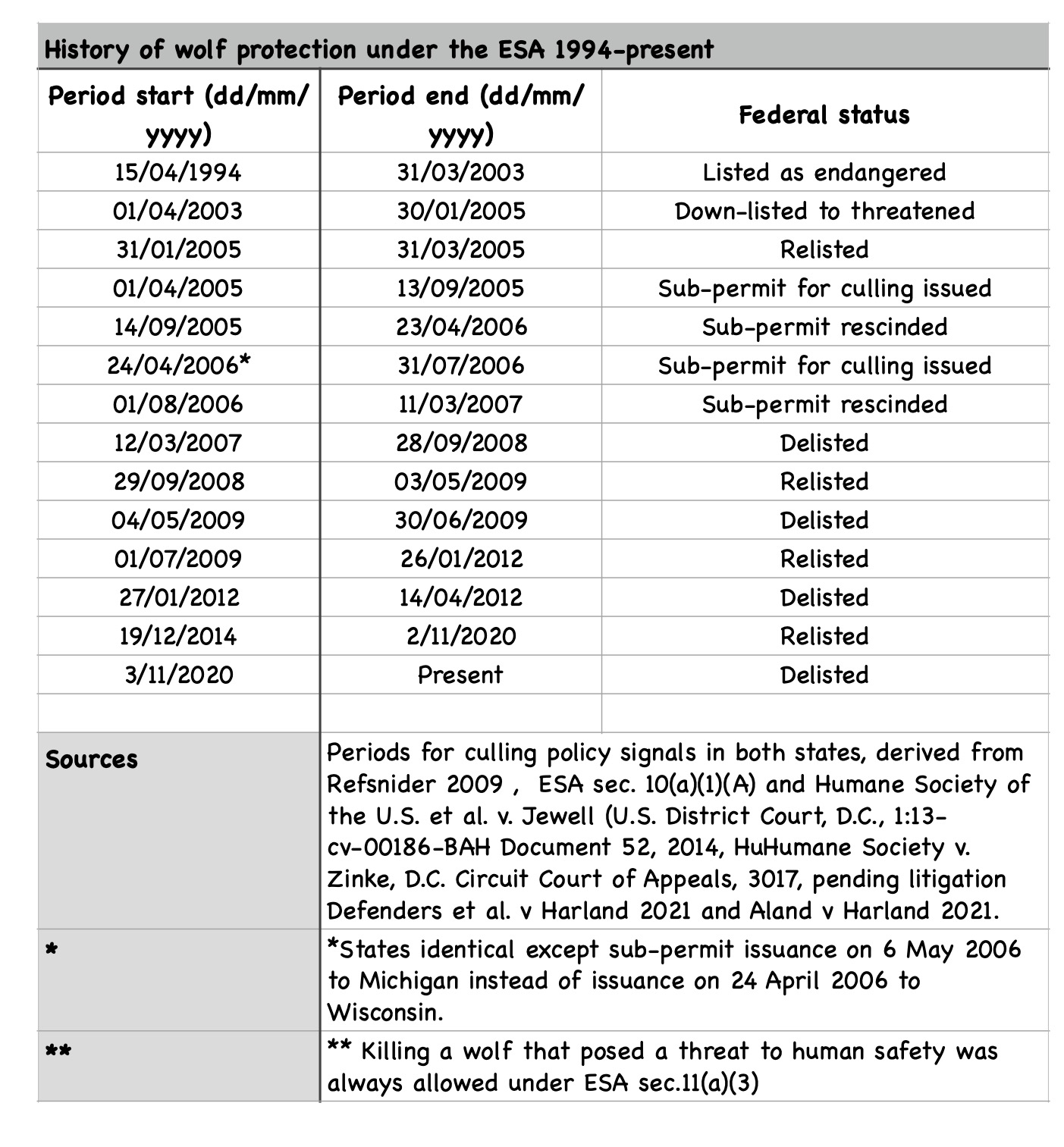

For a summary of court decisions 2003-2012 see a summary table above.