The WBI Process

The challenge that faced the Wisconsin Buffer Initiative was to develop the final recommendations as a collaborative process involving all interested stakeholders. Rather than debate opposing views and perspectives on this contentious issue, these stakeholders were encouraged to define and guide the research process. On-going interaction with UW scientists represented the foundation of the WBI process.

Civic science draws on the idea that many complex issues require a careful interdisciplinary assessment of possible solutions. This type of research and analysis involves well-placed stakeholders who incorporate community preferences and goals as they advise the scientific process.

Science was a critical part of the WBI process, but it is important to place it in the larger context. Wisconsin has the opportunity to use this citizen-scientist, collaborative process involving many and diverse interest groups to seek out innovative solutions to nonpoint pollution concerns. Participants in the WBI process demonstrated that they can be both creative and innovative when answering the previously listed WBI questions.

The civic science process is also consistent with the concept of adaptive management. Adaptive management, as the name implies, means that efforts designed to reduce nonpoint source pollution have to be constructed and organized in a fashion that allows one to learn from both successes and failures. Civic science is also an adaptive management process. During the WBI process stakeholders learned that simply installing as many riparian buffers as possible on the agricultural landscape does not necessarily improve water quality, that confrontation may result in all sides losing and that riparian buffers need to be part of a larger conservation system. These important lessons were carried over into the final recommendations of this group.

WBI Civic Process:

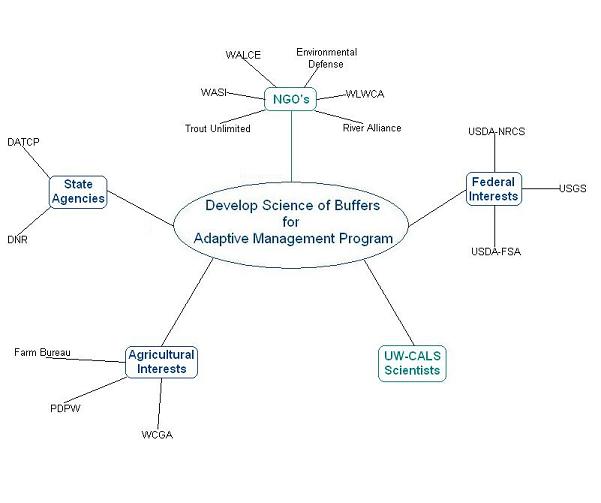

The above diagram models our current collaboration web and portrays the interactions of the Wisconsin Buffer Initiative community.

Committees

The WBI was organized around two key committees. The Advisory Committee, is a diverse group representing all the groups who have an interest in the redesign of the non-point rules as represented in the above diagram. It is composed of scientists from UW-Madison and other campuses, agency staff (federal and state), agricultural groups, conservation associations, and environmental organizations.

An Executive Committee was created with representatives from UW-CALS, the DNR, USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and the Wisconsin Agricultural Stewardship Initiative (WASI). The Executive Committee was charged with providing the leadership to insure that the WBI met the mandate given to it, and to be responsible for the fiscal decisions associated with WBI activities. The Executive Committee met regularly during the initial period of the WBI, but as the Advisory Committee developed confidence in the civic science process, there was little need to make additional executive decisions.

The Advisory Committee was charged with generating the science to answer the four general questions cited earlier. Sub-committees composed of both scientist and citizen were formed on a voluntary basis around each of these questions. The Advisory Committee quickly came to the conclusion that these questions needed to be addressed in a sequential fashion. There are many types of buffers and decisions had to be made as to what type would be applicable relative to the charge from the Natural Resources Board. An extensive review of the scientific literature was conducted to assess the effectiveness of buffers based on both monitoring and modeling methods. There was consensus that buffers will work to the extent they are designed relative to the site-specific conditions and if upland conditions are addressed such that concentrated flow does not run into the buffer.

If buffers will work under specified circumstances, then the next step in the WBI process was to assess where they are needed. This proved to be a complex and difficult decision. Where buffers are placed on the landscape are dependent on two conditions; (1) the current status of the water and associated aquatic ecosystem, and (2) what the goals or objectives are in placing riparian buffers in these locations. After extensive discussions, the WBI Advisory Committee answered the second question first by identifying three priorities for buffer placement. First, and consistent with the mission of the nonpoint pollution program, buffers need to reduce sediment and nutrient flows into the waters of Wisconsin . Second, there was agreement that buffers should be placed in locations where sediment-sensitive aquatic species would benefit. Finally, it was recognized that many of the streams in Wisconsin flow into lakes, reservoirs or impoundments, and buffers should be used to protect these water resources as well. Other objectives such as biodiversity, wildlife habitat, economic impact of a viable trout fishery, and aesthetics were considered, but there was a lack of consensus that these should guide WBI recommendations.

With these goals in mind the committee then turned to examining the current status of the waters of Wisconsin . It was at this point that the Advisory Committee developed a very innovative logic based on available science. The reasoning was that there are some severely degraded waters in Wisconsin where buffers would have little impact. Moreover, it was argued that there are existing federal and state programs that already address these waters. On the other hand they recognized that Wisconsin has some exceptional waters where buffers would also have little impact. When considering the effectiveness and efficiency criteria, the committee reasoned that it is waters in the middle of a distribution that would benefit most from riparian buffers. Consequently, using the three criteria listed earlier (i.e., reduce sediments and nutrients, protect sediment-sensitive aquatic species, and enhance lake water quality), the state was divided into approximately 1600 watersheds and each watershed was ranked on these criteria.

At that point the committee turned its attention to what needs to happen at sites that are selected for buffer implementation. Several "ground rules" were established as part of this process. First the expectation was that local officials and technicians have a better understanding of the situation and would be encouraged to take the WBI recommendations as a starting point. They could revise or adapt these recommendations to better fit local situations and knowledge. Next the committee recommended that in each watershed selected for implementation a local assessment occur. Areas of high biophysical vulnerability should be assessed whether appropriate behaviors are occurring in these locations. Finally, the Advisory Committee agreed that upland treatment of soil erosion and nutrient management has to occur first before any decision is made on whether a riparian buffer is needed.

A final major recommendation made by the WBI Advisory Committee was that riparian buffers be designed in accord with the topographic features of the landscape rather than a uniform strip adjacent to a stream. The logic behind this recommendation is that the buffer has to be designed to prevent concentrated flow from developing in the upland areas.

Funding

Funding for WBI research has come from two primary sources to date. First, the DNR committed $100K to fund WBI research in the initial year and $75K for the second year. Second, UW-CALS worked with environmental groups to get a special allocation ($500K) from the U.S. Congress under the leadership of Senator Herb Kohl. These funds, minus any overhead charges, were distributed based on short research proposals recommended by the WBI Advisory Committee and approved by the WBI Executive Committee.

Sample WBI Research: Research on the Precision Agricultural-Landscape Modeling System (PALMS) model. This model was calibrated and tested on several Discovery Farms in Wisconsin . Results from this research was used to help specify the types of buffers needed.

Research using geographic information system (GIS) technology, on the diversity (physical, biological, land use, social and political) of Wisconsin's landscapes to help guide policy on where and what types of buffers are needed. Research on the diversity of streams and aquatic systems to help determine whether protection or restoration efforts are needed based on buffer technology.

Civic Science Literature

Below is a list of outside literature that has been written regarding the Civic Science Process:

- Tim Allen, et al. 2001. "Dragnet Ecology--'Just the Facts Ma'am': The Privilege of Science in the Postmodern World." Bioscience. pages 475-85.

- Alan Irwin. 1995. Citizen Science: A Study of People, Expertise, and Sustainable Development.

- Alan Irwin and Brian Wynne (eds.). 1996 Misunderstanding Science?: The Public Reconstruction of Science and Technology.

- Daniel Lee Kleinman (ed). 2000. Science, Technology, and Democracy.